The creative repurposing of older, underused buildings has major environmental, social and economic benefits, particularly in the living sectors. But it also has its challenges.

The International Energy Agency predicts the global stock of buildings will double by 2050, with existing buildings accounting for 40% of this stock. Adaptive reuse – which involves repurposing structures, spaces and objects for new functions, effectively extending buildings’ lifespan – is emerging as a key solution that will have a significant environmental impact. Globally, various adaptive reuse projects have demonstrated carbon emissions savings ranging from 40% to 70% when compared with new construction.

Adaptive reuse is part of the circular economy, which the UK Green Building Council defines as an economic model focused on retaining the value of circulating resources, products, parts and materials. This promotes innovative business approaches that emphasise prolonged product life, increased reuse, refurbishment and the use of renewable materials.

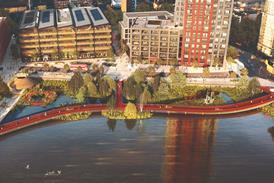

In addition to curbing pollution, adaptive reuse conserves time and resources that would otherwise be expended demolishing and redeveloping structures. It also preserves the social, cultural and heritage value embedded in existing buildings. This cultural impact is not only aesthetic but also economic, as these projects attract businesses, shops and entertainment venues to previously overlooked neighbourhoods. By embracing adaptive reuse, the property industry can contribute significantly to sustainable development, while addressing the pressing issue of global carbon emissions.

But there are some major challenges to this approach. When we first started presenting adaptive reuse of commercial buildings to investors, there was a perception that retrofitting was a lower-risk approach to bringing living schemes forward, compared with ground-up development. This benefit was focused on expediting planning permission, which is an arduous and lengthy process.

While there are planning benefits in terms of density and townscape considerations, there are lesser-realised, but significant, challenges to overcome. The first is often gaining permission for change of use due to loss of employment space. Commercial assets generally sit within employment land and demonstrating that there isn’t a market need for them can be a lengthy and difficult process.

Then there are the challenges with adapting deep floorplates designed for offices into homes. Distance from windows to the building’s core can result in oversized apartments, surplus net internal area (NIA) and shared light between bed spaces and living spaces.

The living sector offering is often combined with build-to-rent apartments and aparthotel flexibility. We have also drawn from the approach of purpose-built student accommodation to smaller amenity spaces shared between certain clusters of units. Developers with a flexible component to the brief can achieve the best use of an asset’s NIA. Clever design of amenities can use ‘dead space’ between the core and apartments, which can be artificially lit, or atrium spaces can be carved in.

However, such building adaptations are complex in terms of structural design. Additional cores and fire safety features will require further structural alterations. Most developers will also seek to add additional storeys to fit in more apartments, but this requires a structural engineer to commit professional indemnity insurance to warranting the safety of an existing structure. With the insurance market so tenuous, advisers and consultants are often wary about providing insurance on historic assets.

Also, in terms of sustainability, older buildings’ energy performance is often inefficient. Achieving Passivhaus standards, which call for airtight buildings with high levels of insulation, takes significant reworking of cladding, windows and ventilation to satisfy regulatory consultants.

But despite these challenges, repurposing obsolete assets is tremendously beneficial both environmentally and for neighbourhoods, where empty buildings deactivate public spaces. While many local authorities recognise this, specific planning policies need to be amended to accommodate retrofitting as the most sustainable form of development. In light of the current energy crisis and need for brownfield urban regeneration, this needs to be at the forefront of the next government agenda for the creation of new homes.

When we do repurpose creatively and effectively, the result is a unique, bespoke and varied living asset that positively supports mixed communities. A thoughtful and ambitious development and advisory team, with skill and commitment, can overcome the challenges to repurposing and bring forward best-in-class brownfield regeneration. It just requires that commitment.

Jo Cowen is chief executive of Jo Cowen Architects

No comments yet